In 2004, it was clear to the fans that the NHL wasn’t going to survive as it was without a decrease in spending on player salaries. After locking out the year for a league, the NHL got a salary cap that gave players a maximum of 57% of hockey-related revenues which resulted in a salary rollback of 24%.

Seven years after the first lockout ended, we’re basically back where we started. The owners say they are losing money and need to cut spending. The players aren’t willing to rollback their salaries again given that the NHL is going through a period of record revenues.

With both sides claiming that the other side is plenty rich enough, we’ve reached another impasse and another lockout. Unlike the last lockout, no one side is right and no one side is wrong. Everyone has played a part in arriving at the latest NHL lockout.

The Players’ Salaries Growing Faster Than The Owners’ Revenue

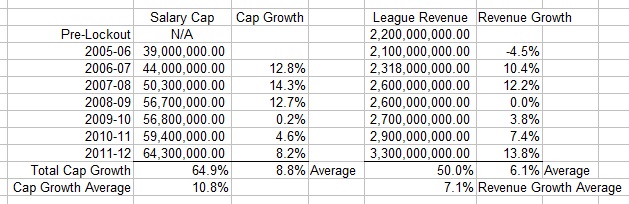

As blog contributor Scott Reaume pointed out to me, the 2005 CBA had a salary cap range from 54% (when HRR is less than or equal to $2.2 billion) to 57% (when HRR is greater than or equal to $2.7 billion). (It’s much more complicated than that but I’ll get to that in a minute.) That has allowed the players’ salaries to grow faster than hockey-related revenues. While I realize that the owners were dumb enough to allow the players to grow their take faster than they could, the players can’t say that they are hard-done-by under the current system.

The other factor that allowed the cap to increase faster than league revenues is the NHLPA’s 5% escalator in the cap calculation. Per Article 50.5 (b) (iv) of the 2005 CBA, the prior season’s HRR is used to calculate the midpoint per team for the upcoming season. The 5% escalator is then applied to that midpoint to come up with the final midpoint. This is an optional escalator that the NHLPA can for go but they have not used the escalator only once over the course of the CBA.

Per a Canadian Press article about the 2011-12 salary cap, the 5% escalator is in place to combat the effect of inflation. However, since 2004 (the year before the lockout), the average annual inflation rate is 2.4%. In other words, the players are getting the league’s revenue growth, inflation and an extra 2.6%.

When you look at my comparison of revenue growth versus cap growth, you can see that the cap grows at a rate faster than revenue growth in the prior season. That’s because of the 5% midpoint increase that the NHLPA has gladly taken advantage of five out of the six opportunities they’ve had to exercise it.

So while the NHL touts their economic success and record revenues, the CBA seem to have resulted in the owners giving it right back to the players faster than they were bringing it in. Sure, the escrow fund the players pay into to prevent overspending helps mitigate the possibility that owners overpay players compared to the revenue coming in. In a perfect world, the escrow would ensure players are paid exactly what they are entitled to and no more. However, in a world where Ilya Kovalchuk’s cap his is over $4 million less than what he’s actually being paid, who knows if the escrow applies to cap hits or cash outlays. There’s too much opacity for the fans to know who is actually getting the short end of the stick.

The Salary Floor Also Drives Up The Players’ Share

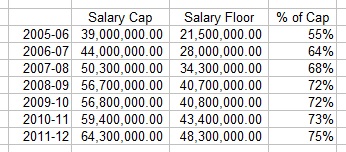

If you’ve read the CBA, the salary cap and floor aren’t explained in the most straight forward way possible. There’s a specified midpoint that is calculated from which a team can’t spend $8 million more or less than. In other words, the $16 million gap from cap to floor is defined as $8 million from the cap to the midpoint and $8 million from the midpoint to the floor.

In 2005-06, the cap and floor were set at negotiated, pre-determined amounts. From 2006-07 onwards, the calculations specified in the CBA determined the cap and floor. As a result, the floor as a percentage of the cap as increased from 55% in 2005-06 to 75% of the cap in 2011-12. In other words, whether they can afford it or not, teams are being forced to spend more money in terms of a percentage of their revenue and actual dollars.

While the cap going up has resulted in an increase in spending as teams spend money to attract/keep players, it’s the growth in the floor that’s causing more problems. While teams don’t have to spend to the cap, they have to spend more than the salary floor. As that above table shows, the floor is growing relative to the ceiling in terms of percentage. Teams are forced to overspend on mid-level players to reach the floor which drives up the costs of all players.

The Owners Agreed To This Too

While the players have a very favourably calculated salary range under the outgoing CBA, it’s not their fault that they’re taking advantage of it. The CBA is an agreement between the players and the owners. As such, the owners agreed to a set of circumstances that they could have foreseen would have essentially allowed the players’ portion of revenue to grow faster than revenue grows.

It’s hard to be sympathetic to a group of people who are supposed to be smart but come out of negotiations looking like morons. They thought they won the last labour fight but hindsight shows that the NHLPA got the better deal. Sometimes you out negotiated. Now they have to correct the balance of the CBA so both the players and owners get a fair amount that allows the franchises to economically viable without over or under-paying the players.

The Owners Are Asking For An Overcorrection

The owners are planning to correct the issues they have with the current CBA by trying to undo all the changes made since expansion in 1967. Eliminating salary arbitration and extending the time for which a player would be considered a restricted free agent to 10 years could bring the NHL back to the days when players were essentially owned by one club with free agency being non-existent. Players would essentially be held hostage for the first ten years of their careers unless the virtually unused offer sheet is used by another team to sign them.

That last paragraph doesn’t touch on the new five-yeal entry-level contracts which would effectively cap the earnings of new players at $18.9 million for their first five years (assuming the ELC max of $3.775 million per year including bonuses). While that’s still more money than most of us will ever see in our lives, it does limit a player’s career earnings potential when compared to a player who finished up their ELC this past season.

The owners are also trying to protect themselves from themselves by capping contracts to a five season maximum length because of all the front-loaded, long-term contracts they hand out like candy at Halloween in order to lower short-term cap hits. With a five season cap, it’s unlikely that players will see those massive contracts with annual salaries of greater than $10 million because it would ruin a team’s cap situation. This would be the owners punishing players for the owners exploiting a loophole in the CBA that allowed them to entice players to sign with them by throwing money at them.

The initial proposal of giving players 43% of HRR would have slashed players salaries by 24% from the current 57% of HRR. Coincidentally, player salaries were rolled back by 24% when the outgoing CBA was introduced in 2005. The owners say they lost $240 million in total over the last two seasons. Based on the table below, the owners will save that amount in player salaries by dropping the players’ percentage of HRR to 53% percent which would represent the players losing 7% of current salaries. That doesn’t include the change in the definition of hockey-related revenue that the league initially proposed which would decrease the revenue pool that would be used as a basis for the salary cap.

Basically, the owners are trying to save themselves from themselves with their ridiculously low initial offer. The press have reported that they’ve brought their offer up to the 47% to 49% range. While the league is moving away from changing the definition of HRR, nobody has mentioned if the NHL has stopped asking for shorter contracts and a longer service period before unrestricted free agency. The NHL’s latest offer is an improvement in terms of dollars but not necessarily in terms of the total package.

Helping Failing Franchises Should Take Priority Over A League-Wide Spending Cut

There is no question that some NHL franchises need some help to be viable. It’s not all 30 teams who need help. It’s the franchises with low revenue that need to be helped. Teams like Phoenix, Florida and the Islanders, among others, aren’t the wild successes that the NHL likes to tout when talking about growth.

If the NHL wants to make the league heathy, that means all the franchises need to be healthy. Otherwise, we’ll be back in six years with the owners crying poor again. The league needs to do two things to improve the health of these have-not franchises.

First, the league has to increase the revenue sharing pool and make it available to the teams that need the help. The NFL and MLB already have extensive revenue sharing programs that ensure that all the teams in the league have a chance to be viable/profitable. The NHL does have a revenue sharing program but with Atlanta having just moved and it being nearly impossible for the league to sell the Phoenix Coyotes, there is clear evidence that not all franchises are viable as things currently stand.

Secondly, the league has to be willing to admit that there are more economically viable markets than some of the ones they’re in. New arenas that are being built to attract NHL teams are going up in Quebec City, Markham and Seattle. Kansas City has a new arena that’s been sitting around without a regular tenant for the last five years. Given that the league as a whole has lost an average of $120 million over the last two seasons, it’s clear that the status quo isn’t perfect. While revenue sharing can help some of the franchises who are losing money, some (Hi, Phoenix!) are absolute lost causes and need to be moved to be saved. Moving these lost cause franchises will help improve the league’s finances as a whole.

If Either Side Actually Cares About Hockey Or The Fans, They’ll Negotiate

The words I read most often when it comes to CBA “negotiations” are “proposal,” “offer” and “counter-offer.” In order to get this done as quickly as possible, owners and the NHLPA need to sit down in a room and sort out what they disagree on. The key is that they actually have to engage in a dialogue in order for there to be negotiations. Right now, the process comes off as NHL offer, NHLPA dismissal, NHLPA offer, NHL dismissal and rinse and repeat.

The biggest problem with the current state of negotiations is that there is no one trying to facilitate a dialogue because everyone involved is looking out for their own interests. The players have Donald Fehr representing their interests. The owners have Gary Bettman representing their interests. The NHL, the game of hockey and the fans have no one representing their interests. Both the owners and players claim to be in it for the fans but neither side care more about the fans than themselves.

The NHL CBA negotiations need a third party to aid the two sides in moving toward an agreement. Either Bettman has to stop representing the owners and become a mediator between the two sides or he has to bring in an outsider to act as a mediator. Having Bettman represent both the league and owners (who are separate from the league) in a negotiation seems like a conflict of interest to me.

We’ve already lost games twice to lockouts with Gary Bettman as commissioner. Let’s not to lose games a third time.

References:

League Revenue – Pre-Lockout, 2005-06, 2006-07, 2007-08, 2008-09, 2009-10, 2010-11, 2011-12)

Canadian Inflation Rate (CPI) – Stats Canada

NHL losses over last two seasons – Pro Hockey Talk

5% salary midpoint escalator – CBC Sports

One thought on “There Is No Right Side In The 2012 NHL Lockout”